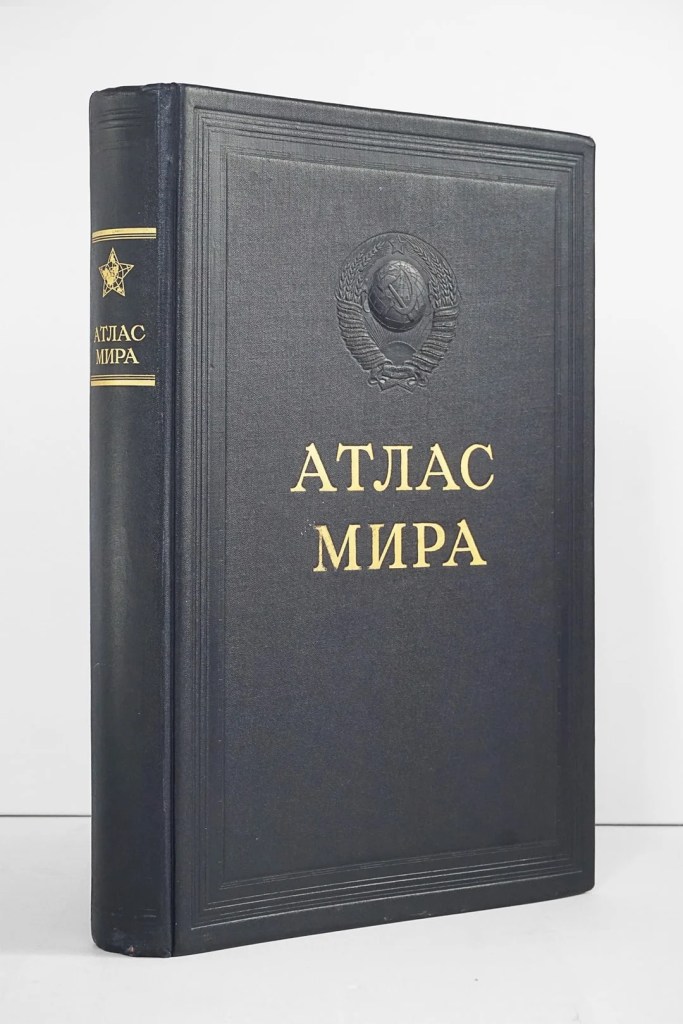

The Atlas Mira (Атлас мира, “World Atlas”) is one of the most ambitious state-level cartographic projects of the 20th century. It is considered an achievement due to its scale and ambition. It was a Soviet effort to produce a comprehensive, authoritative atlas of the globe. The goal was to compete with Western world atlases. It also aimed to serve domestic administrative, educational and ideological purposes.

The large first edition was published in 1954. A revised/Anglicized second edition was released in 1967. It was issued in Russian. There was also a contemporary English version often titled The World Atlas. Around 1999/2001, a late-Soviet/post-Soviet third edition was released. These editions mark clear shifts in production techniques, cartographic priorities, and political messaging. This article compares those three editions. It documents known print runs and offers both a technical cartographic reading. It also provides a political analysis of how mapping choices show changing priorities in the USSR and post-Soviet Russia.

Quick facts (editions & print runs)

- 1st edition – 1954: A two-volume, heavy folio atlas (maps + separate index volume). Large format, lavish relief tinting and double-page spreads; reported print run 25,000 copies.

- 2nd edition – 1967 (Russian) / 1967 English translation: The layout was revised. Somewhat fewer pages were devoted to the USSR because a separate Atlas of the USSR had been produced. It was published at the same time in Russian and English. Reported print run around 25,000 copies for the 1967/68 edition(s). Scans of the English edition are held in the David Rumsey collection.

- 3rd edition – 1999 (and reprints 2001 etc.): This edition is a modernized single-volume atlas combining maps and index. It is updated to late-20th century political boundaries. It also features more contemporary cartographic aesthetics. Marketplace listings indicate later printings in the tens of thousands. One listing cites a print run figure of approximately 27,300. Editorial lead for the modern edition: T. G. Novikova.

(These print-run numbers are from publisher records and bibliographical / marketplace sources aggregated by cartographic libraries and collectors. Exact official Soviet archival records are scarce in the public domain. The figures above are consistently cited in bibliographical descriptions.)

Form and production: how the editions differ physically and cartographically

Format, scale choices and paper

The 1954 Atlas Mira was produced with a very large format. It had a weight reportedly about 7 kg and nearly 50×33 cm in size. It came with two volumes, a map volume and an index volume. Many maps are printed as large double-page spreads. Relief is shown using hypsometric tinting with contour lines. There is occasional shaded relief, which gives a “raised” visual effect. This style was popular in mid-century cartography. The atlas uses many large-scale regional sheets. These sheets are as detailed as 1:250,000 for urban insets. They can be 1:1,250,000, 1:2,500,000 and 1:5,000,000 for various areas. This edition was intended as an authoritative research/administrative reference as much as a public atlas.

By 1967, the production refined the palette. It standardized sheet sizes slightly smaller than the massive 1954 folio. The production also introduced a more consistent use of 18 color tints. There was a pronounced use of relief shading combined with contouring. A separate Atlas of the USSR had been issued in the intervening years. Consequently, the second edition reallocates space away from exhaustive Soviet regional detail. It provides a more globally balanced set of maps, introducing at least a dozen new/rewritten maps versus the 1954 plates. The English edition printed simultaneously indicates the Soviet intention of projecting cartographic authority abroad.

The 1999/2001 edition modernizes the look. It features a single-volume layout combining maps and index. Place-names are updated to reflect post-Cold War country names and borders. Hypsometric and terrain modeling are digitally revised to match late-20th-century cartographic printing processes. The index is expanded to include around 240,000 place names. The later edition reflects the shift to computer-assisted cartography and new lithographic standards available after the Soviet era.

Projection, relief and cartographic technique

Across all three editions, the Atlas Mira favors classical cartographic projection choices. These choices are suitable for a world atlas with general world maps at small scales. They include continent maps, mid-scale regional sheets, and localized large-scale insets. The first and second editions emphasize hypsometric tinting combined with shaded relief and contouring. This combination produces strong three-dimensional visual cues.

These aesthetic choices make physical geography visually legible and monumental. The 1967 edition is especially noted for its rich color separations. It is also recognized for careful printing techniques. Special cartographic paper and inks were reportedly used. The 1999 edition preserves the hypsometric approach. It benefits from improved digital elevation models and printing fidelity. These enhancements create smoother, more consistent relief rendering.

Indexing and Toponymy

The index grows and changes across editions. The 1954 edition’s separate index volume lists about 205,000 entries. By the 1999 edition, the combined atlas+index volume lists roughly 240,000 names. This increase is a product not only of editorial work but also of geopolitical changes. Expanded gazetteer data accumulated during the second half of the 20th century contributed as well. Transliteration and toponymic choices also change. The English 1967 edition uses transliterations and anglicized forms for international readers. In contrast, Russian editions use Soviet orthographies and naming conventions. These choices implicitly communicate which names are authoritative. They also reveal which languages get primacy. Lastly, they show how foreign places are presented to Soviet and foreign audiences.

What changed politically from edition to edition: reading the map as statement

A state-sponsored world atlas is simultaneously a scientific artifact and an instrument of soft power. The Atlas Mira is no exception. Cartographic decisions are political choices. These include what gets emphasized, what gets reduced, what names are used, and what borders are drawn.

1954: early Cold War cartography: consolidation and projection

The 1954 Atlas Mira appears in the early post-Stalin years. It was published shortly after Stalin’s death. It functions to consolidate Soviet cartographic prestige. The enormous physical format is impressive. There is a separate index volume. The atlas heavily emphasizes the USSR and its “friendly” zones, notably Eastern Europe and China. These features communicate both technical mastery and political centrality.

The atlas frequently treats the USSR in near-continental terms. Separate Soviet Republics have administrative maps. They also have transport maps, time zone treatments, and high-detail insets. This cartographic privileging makes a bold political statement. It shows the USSR as not only large but also cartographically central. The USSR deserves a thorough, multi-faceted depiction. It should rival any western counterpart. The contents and the frontispiece vignette (a world map inside a five-pointed star) are explicitly symbolic.

1967: détente, outward projection, and audience diversification

By 1967, the Soviet state had both internalized its post-war stature and attempted to address an international audience. The simultaneous Russian and English editions show a deliberate attempt to export Soviet geographic knowledge. This was a way to say “we can map the world as authoritatively as any Western house.” The relative reduction in the number of USSR-specific sheets occurred because of a dedicated Atlas of the USSR.

The introduction of new global maps suggests the editors were calibrating the atlas for foreign use. They aimed for global intellectual competition. Printing a high-quality English edition was an act of cartographic diplomacy. The atlas could be used in libraries, embassies, and universities worldwide. It presented Soviet perspectives on borders, names, and geopolitical divisions.

Cartographically, the 1967 edition’s careful color work and improved consistency present a professional face to the world. The political choices, such as which breakups or non-recognized states are displayed, still reflect official Soviet positions. How disputed territories are labeled also reflects these positions. For example, the prominence and detailed plotting of Eastern Bloc transport corridors are evident. The depiction of Communist allies is also significant. Furthermore, the treatment of colonial territories, still numerous in 1967, informs a reader looking for geopolitical subtext.

1999: post-Soviet revisionism and technocratic modernization

The third edition (c. 1999/2001) arrives after the USSR’s dissolution. Its cartography must contend with a very different political reality: new independent states, redrawn borders in Eurasia, changed place-names (e.g., renaming of cities and restoration of historical toponyms), and an international preoccupation with newly emergent states and disputed spaces. The atlas therefore performs a dual function. It is an inventory of the post-Cold War world. It is also an act of national cartographic continuity. The Russian state asserts that it retains authoritative cartographic skills. It claims the right to define the world spatially.

From a political perspective, the 1999 edition is less ideologically propagandistic in visual rhetoric than the 1954 edition. However, it is still a statement. Russia remains a central cartographic actor. The editorial choices about place-names, transliteration policies are especially sensitive. The depiction of newly independent former Soviet republics also communicates a political stance. It may reflect neutrality, paternalism, or renewed influence. The switch to a single-volume atlas reflects technical modernization. An updated index reflects changed expectations of atlas use. There is now more reference and broader public access.

Specific cartographic differences: three concrete examples

- Treatment of the USSR and its administrative detail

1954: Many union-republic level maps and city insets are included. Transport layers also offer detailed insights. The USSR is treated almost as a separate “continent.” 1967: The atlas includes fewer USSR plates because a dedicated USSR atlas exists. This makes room for a more global balance. 1999: The USSR is no longer pictured. However, the atlas devotes careful attention to newly independent states. It details their administrative boundaries. These editorial reallocations are both cartographic and political decisions about emphasis. - Disputed territories and toponymy

The 1954 and 1967 editions reflect Soviet diplomatic positions of the era. These positions influence how disputed regions are labeled. For instance, they affect the treatment of Palestine/Israel in mid-century editions or the colonial possessions of Western powers. The 1999 edition updates these treatments to reflect new sovereignty claims and the post-colonial world. Changes in transliteration schemes (Cyrillic→Latin renderings) occur. They mark a shift from Soviet orthographic norms toward conventions more acceptable in international publishing. (See English 1967 edition scan for transliteration patterns.) - Relief and printing technology

The 1954 edition’s bold hypsometric tints and contour work were crafted by painstaking hand techniques. Lithographic techniques were also used. The 1967 edition refined the color palette and printing methods. The 1999 edition uses late-century digital production techniques and better elevation datasets. This yields smoother and more consistent terrain visualization. The shift is visible to any side-by-side reader and marks the transition from analog to digital cartographic craft.

The Atlas Mira as soft power: intended audiences and uses

The Atlas Mira had multiple target audiences across editions:

- Domestic bureaucrats, planners and academics needed authoritative references for teaching, planning and governance. The 1954 edition was especially useful with its deep Soviet coverage.

- International audiences and libraries were especially targeted by the 1967 English edition. It was a geopolitical tool intended to demonstrate Soviet technical competence. It also aimed to promote Soviet geography as academically valid in Western institutions.

- A new post-Soviet public appeared in the 1999 edition. They include general reference users, educational institutions, and state agencies. These groups require a modern, consolidated atlas reflecting the contemporary world order.

The very act of producing a high-quality world atlas is an assertion of legitimacy. The state that publishes the atlas declares that it knows the world as it should be known. In a Cold War context that claim is inherently political.

Where bibliographic certainty is strongest, and where gaps remain

There is a reasonable bibliographic consensus on the edition years (1954; 1967; 1999/2001). There is also agreement on many formatual and editorial differences (two-volume 1954, reduced Soviet plates in 1967, single-volume modern edition). Multiple authoritative collections, such as national libraries, hold scans for the 1967 English edition. The David Rumsey Map Collection includes bibliographic entries as well. Specialist atlas bibliographies document the editorial credits (A. N. Baranov as editor for the early editions; T. G. Novikova for the 1999 edition).

Print-run figures are documented repeatedly in collector and bookseller descriptions. A figure of 25,000 for the 1954 and 1967 editions is commonly cited. Additionally, a late-1990s print run figure around 27,300 appears in marketplace notes. Those numbers align across multiple bibliographic entries. However, they should be understood cautiously. Soviet publishing records can be opaque. Bibliographic entries sometimes repeat the same secondary source. If precise archival confirmation of initial press runs is needed, you should conduct a deeper search. To gather this information, you need to search the archival records. Specifically, look into the archives of the Chief Directorate of Geodesy and Cartography (GUGK, Главное управление геодезии и картографии). Additionally, examine Russian publishing archives.

Practical recommendations for collectors and researchers

- If you want an original Cold War artifact: seek the 1954 two-volume atlas. It is physically imposing, historically resonant, and the edition most saturated with the iconography of early post-war Soviet cartography. Be prepared for heavy folio sizes and to verify completeness (maps + index volume). There are many market copies (booksellers and auction listings cite 25,000 copies printed, so they turn up in collections).

- If you need a researchable English copy for citation or classroom use: use the 1967 English edition. This edition of The World Atlas is useful. There are scanned copies in map collections (David Rumsey). These can be consulted for translation and for comparison with contemporary Western atlases.

- If you want a contemporary, single-volume, updated reference: the 1999/2001 edition will contain more modern toponymy. It will reflect late-20th century political geography. This edition retains the Atlas Mira’s visual language. Market listings indicate later printings in the tens of thousands, making it more accessible.

Final assessment: cartography and politics intertwined

The Atlas Mira is a vivid reminder that atlases are never purely technical artifacts. Across its three major editions the atlas demonstrates:

- Cartographic excellence — high production values, careful relief work, and professional cartographic conventions. These match or exceed many contemporary Western atlases. The Atlas Mira’s maps are technically sophisticated. They include thoughtful scale hierarchies and large double-page cartographic plates. A rich hypsometric palette makes physical geography legible and dramatic.

- Political authorship — the atlas projects Soviet (and later Russian) perspectives. It begins with the mid-century emphasis on the USSR as a cartographic centerpiece. The 1967 edition reaches out to an international audience. The 1999 edition re-stages Russia as the inheritor of a cartographic tradition. Each edition embodies political time. The 1954 atlas asserts consolidation and state power. The 1967 edition projects competence abroad. The 1999 edition re-frames Russia as a modern mapping authority in a changed world.

- Continuity and change — editorial teams changed, technologies advanced, and geopolitical realities shifted. However, a through-line remains. The Atlas Mira was conceived as a national cartographic flagship. The ambition is to produce a definitive world atlas in large-format. It maintains an authoritative style. This ambition unites the editions even as their emphases and designs evolve.

Sources & further reading

Selected sources used in this article (scans, bibliographic records and specialist atlas notes):

- English Wikipedia: Atlas Mira (summary of editions and production notes).

- David Rumsey Map Collection — scans and catalogue entries for the 1967 English edition (The World Atlas).

- Atlaseum (detailed atlas page for Atlas Mira 1954 and The World Atlas 1967).

- Various Russian book listings and bibliographic pages documenting format and reported print runs (e.g., Moscow books / antiq Russia listings).

- Atlassen.net — bibliographic overview of the three major editions (1954; 1967/68; 1999/2001) and editorial credits.